The main

interest and focus of this series will be the analysis of licensed properties

which have sought to expand the Star Wars

story. While these works contribute to the same fictional universe as the Star Wars movies, they are not

necessarily considered part of the story’s official timeline. Since they are

not granted the same level of credibility as the movies, any works classified

as “expanded” works make up a fictional universe all their own, one with a much

richer history than what was exclusively established by the films.

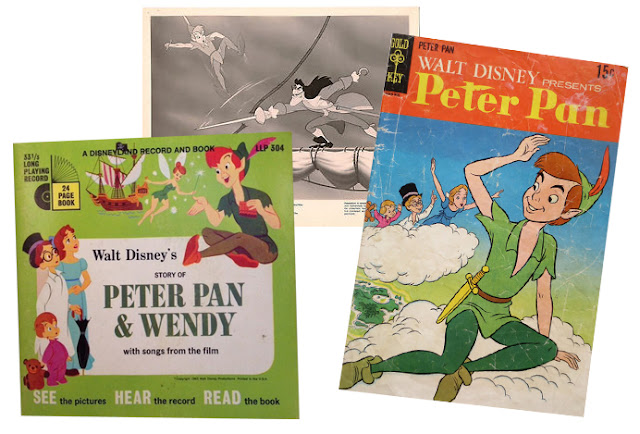

The Star Wars Expanded Universe began with

Edward Summer, a fellow filmmaker and friend of George Lucas who served as a

marketing consultant on the original Star

Wars film. Lucas and producer Gary Kurtz were extremely interested in

Disney’s marketing model. Summer, who had a number of Disney press kits in his

collection, showed many of them to Lucas and Kurtz. According to Summer, the

marketing of Peter Pan was

particularly masterful and stood out to them. That film enjoyed a massive

amount of marketing and merchandising, including comic books, toy tie-ins, and

games. This initially served as the model for how they intended to market Star Wars. Although none of them

realized it at that time, it also served as the genesis of the Star Wars Expanded Universe.[i]

Lucas Licensing

oversaw the creation and publication of countless Star Wars stories in printed media, during the production of the

original films and long after. The effort was less structured at first, but

eventually these stories developed their own intersecting storylines,

legitimizing them as genuine contributions to the Star Wars universe. This ongoing effort to maintain the Star Wars mythology outside of the films

was branded, and is now popularly known as, the Expanded Universe.

Like our own

universe, the Star Wars mythology is

an ever-expanding and sometimes contracting world of limitless possibilities.

Also like our universe, there are conflicting theories and debates concerning

how or why (or even if) this occurs. It sounds more like physics than fiction,

but that parallel is one of the reasons I find myself fascinated with the subject

in the first place. When fiction creates worlds, mythologies are born.

So the question

really is...

What is a mythology?

As a point of

clarity, I am defining the mythology of a story based on the themes and motifs

discussed in the works of Joseph Campbell, specifically The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Any story that creates worlds and

explores universal themes within those worlds is, to some extent, a mythology.

What we will focus on as we examine the Star

Wars mythology is how that story creates for us a new expression of the

mythical hero’s journey. This is in part because Campbell’s work on the subject

is as definitive as any work I know, but also because his study of the hero’s

journey was a direct influence on George Lucas when he created Star Wars.

The existence of

an expanded universe in any franchise hints at the existence of a greater

mythology in the core story. While often enough “expanded” works offer little

more than repetitions of the larger story in a smaller medium, some franchises

have managed to advance the mythology even in the absence of an ongoing

incarnation of the core story.

Put simply, that

means that franchises like Star Trek and

Star Wars can be sustainable even

during considerable periods of time where there are no movies or television

series being produced. Stories told in other media - such as novels or comic

books - fill in the gaps between larger productions, even though such stories

rarely enjoy any attention or contribution by the original creators of the

franchise.

Mythology at the

most basic level comes down to two things: The complexity of the universe that

is built around the story and the simplicity of the themes explored within the

story. The universe in which Star Wars takes

place could not be more alien to us cosmetically, but when we examine the problems

and dreams of Luke Skywalker, we cannot help but feel that at his core he is

not very different from us.

The core story

in a fictional universe is focused on themes that are to some degree universal

to all audiences. The story at this level is told in mainstream media that will

appeal to the largest audience, for obvious reasons.

So before we go

into the thematic construction of mythologies, it’s more important for us to

focus on the process of world-building. The mythos of a story is determined by the

scope of the universe it creates and the richness of that universe. Scope

defines size while richness defines detail. An epic story requires scope, but

its mythical qualities are defined in the details.

Continuity vs. Canon

The scope of a

story is defined and ultimately regulated by rules that determine both the

potential and the limitations of the world they govern. These rules are not

overtly stated and are generated over time by events that occur within the

framework of the story. As these events unfold, they create an intuitive

understanding of what is and isn’t allowed in that universe. If this is not

part of a larger plan (which it usually isn’t), how do these universal laws

just organically manifest?

I think in order

to answer that question it’s important to explain the difference between

continuity and canon, because they are the most commonly cited governors of

mythological world-building. Often these terms are used interchangeably, but

they are not the same thing.

Continuity

refers to the level of consistency that can be expected from one installment of

the story to the next. It is quantitative in that it governs the basic

constants of the universe. That James Kirk’s middle name is Tiberius is a

matter of continuity, as is the fact that he is from Iowa and he serves on a

spaceship called the USS Enterprise

in the twenty third century. Someone has to remember from one episode of Star Trek to the next that these are

part of the story’s universe. If this is not done, then the universe is only as

big or as small as it is in the episode you are currently watching, and your

investment in the story is managed accordingly.

Continuity is essentially the record of what has happened in the history of the story, incorporating all information contributed to the universe in the course of those events. When previously established details are later contradicted, the integrity of that history is called into question and the story illusion is jeopardized.

Continuity is essentially the record of what has happened in the history of the story, incorporating all information contributed to the universe in the course of those events. When previously established details are later contradicted, the integrity of that history is called into question and the story illusion is jeopardized.

Canon performs a

similar function, but is a much newer construct as a storytelling device. Canon

is less concerned with specific content as it is with the context of the story

as a whole. Continuity is quantitative, describing the timeline of what

happened. Canon is a qualitative concept, informing our abstract understanding

of the message those events are meant to communicate. In its subtler form,

canon guides our perception of what transpires within the continuity of the

story. In its more intrusive aspect, canon is also used to determine whether

certain events belong in that continuity, regardless of whether or not those

events occurred in an episode of the story that has already been presented to

the audience. Canon sometimes follows the dubious pretext that what was heard

is not always what was said.

It’s complicated

enough when this process follows the events within a single story, even if the

story unfolds in an ongoing series of individual episodes. When you’re dealing

with a franchise that spans several media outlets and formats, many of which

are not created or directly supervised by the original author of the work,

there comes the question of how a story in the expanded mythology is to be

considered. Specifically: What makes a story canonical (meaning that it is

officially regarded to have actually happened)?

There are a lot

of different approaches to how the canon of a fictional universe is developed,

but in the broadest sense it is generated by an indirect creative collaboration

between the story’s creators and its audience. Writers put forward certain

ideas and they are either embraced by the audience and therefore ratified, or

they are rejected and eventually overwritten. This shared concept of what makes

the fictional universe function is generally recognized as its canon.

Canon is not a

function of the mythological aspect of storytelling because if a story is

mythological in tone, the themes within it should already be inherently

understood by the audience. For this reason I will go over what is considered

canon as we discuss various expanded works, but the relative canonicity of

those works will not in any way impact my analysis of them or their place in

the Star Wars mythology. I’m more

interested in the content of the stories as it was originally presented.

Expanding Universes

Star Wars is a movie. Star Wars is a series of books. Star Wars is a series of comic books and

newspaper comic strips as well as television movies, series, and specials. In a

universe that broad, what is “real” and what isn’t? Is all of it real? What if

one story contradicts another? What if a future movie contradicts what is said

in one of the expanded stories? These are not questions that really got asked

back in 1977, but people were slowly starting to decide that they should be.

Star Wars and Star Trek were the first major franchises to address the question

of a comprehensive canon because they were the first franchises to fully

develop their own expanded universes. Corporate entities licensed out

properties as a marketing tool long before Gene Roddenberry and George Lucas

came along, but in the case of Star Trek and

Star Wars we see the first instances

where the original creative force behind the story worked to retain enough creative

control to insure the overall integrity of their fictional universe.

They approached the

challenge in distinctively different ways. Gene Roddenberry, creator of Star Trek, considered the television

series and subsequent films to be “Star

Trek fact” (canon) and all licensed properties like the myriad novels and

comic books to be “Star Trek fiction”

(non-canon). The creative teams behind the licensed properties were forbidden

to maintain any continuity of characters and events with each other or indeed

to develop original characters and continuity on their own. The Star Trek Expanded Universe, such as it

was, served merely as a money machine for the various corporations that owned

it. Gene Roddenberry had his research assistant, Richard Arnold, work with the

Paramount licensing office to make sure the expanded works didn’t contradict

the film canon, but there was no concept of an expanded canon that could stand

on its own.[ii]

The same could

be said for the Star Wars Expanded

Universe, but the methodology was significantly different in how it would be

regulated. An absolutist would argue that the only true Star Wars canon would be the films, and everything else is just a

different interpretation of what might have happened outside the films. But

this is not the case in terms of how expanded stories are classified in Star Wars canon.

It all comes down

to control. The amount of control that Roddenberry and Lucas wanted to exert

was roughly the same, as were their reasons for it. They believed in their

creations and wanted to protect the brand they represented. But Gene

Roddenberry didn’t own Star Trek. His

role in terms of how its canon was developed was almost ceremonial. He was a creative

consultant, but Star Trek was

licensed out to unrelated corporate entities with or without his approval.

On the other

hand, Star Wars was owned by a single

person. 20th Century Fox owned the original film, but George Lucas

owned and controlled all interests concerned with licensing and merchandising.

Because Lucasfilm controlled the Star

Wars Expanded Universe, Lucas Licensing could put a lot more effort into

developing it. To that end they created a model that would be more flexible to

the creative process of its contributors and a lot more satisfying to the fans.

George Lucas was just as concerned with protecting his story as Gene

Roddenberry had been with his, but Lucas also had a financial interest in assuring

that the licensed properties had enough creative freedom to be successful in

their own right.

At times it felt

like Gene Roddenberry would deliberately hamstring the creative teams working

on Star Trek licensed properties,

because the expanded works were a necessary evil whose success was of no direct

benefit to him.[iii]

The Star Wars Expanded Universe was a

departure from that methodology because Lucas had full creative and financial

control of it. That distinction is significant, because it meant Lucas had the

unique opportunity to construct a fully-functioning multi-platform fictional

universe with himself as the final judge of what would go into it and the

primary beneficiary of everything it produced.

The Star Wars Expanded Universe was the

first consciously engineered and carefully cultivated expansion of a fictional

mythology. Because its success as an entity has always been a priority, we as

an audience have benefited from the creative directions the Expanded Universe

was allowed to take. Its actual contribution to the overall mythology has

always been questionable, but it was allowed to be self-sustaining as a

microcosm within that mythology, and that’s worth studying too.

READ EXPANDING UNIVERSE VOLUME 1 NOW!

[i]

Edward Summer said this in “Summer Blockbuster,” an

interview with JW Rinzler in Star Wars

Insider #140, April 2013, p.

53.

[ii]

In the Hailing

Frequencies Open editorial page of Star Trek #1 (DC’s 1989 comic series), series editor Robert

Greenberger explained some of the restrictions dictated by Paramount’s

licensing team and Gene Roddenberry’s office, including a prohibition against

using any original characters created for their previous Star Trek comic book. The decision had also been made that the Star Trek animated series, which had

previously been considered canon, was no longer considered canon and therefore

the characters from that series were also off-limits.

[iii]

In the Hailing

Frequencies Open letters column of Star Trek #5 (DC’s 1989 comic book series), a fan letter condemned Gene Roddenberry’s research assistant Richard

Arnold for forcing the DC creative team to dump their original secondary

characters and focus only on main characters. Robert Greenberger was quick to

clarify that Richard Arnold spoke on behalf of Gene Roddenberry, so those

dictates did not come from Arnold but from Roddenberry himself.

No comments:

Post a Comment